Since the Queensland Art Gallery opened in 1982, the Cultural Centre has evolved into the arts and culture centrepiece of the state. The Gallery and the Cultural Centre is architecturally significant and demonstrates the evolution of modern landscape architecture in Queensland. Having recently entered the Queensland Heritage Register, we look at the many proposals to get to where we are today.

Throughout the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the major Queensland cultural institutions were accommodated in a range of facilities throughout Brisbane: the Queensland Museum and the Queensland Art Gallery in the Exhibition Building on Gregory Terrace, the State Library in William Street while performing arts companies utilised a variety of venues including the concert hall in the Exhibition Building, Her Majesty’s Theatre, and the City Hall (from 1928).

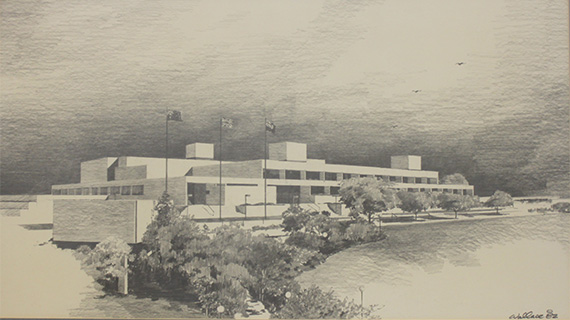

Architectural drawing, Queensland Art Gallery, 1982

Architectural drawing, Queensland Art Gallery, 1982

PROPOSALS FOR A CULTURAL CENTRE: 1800s – 1960s

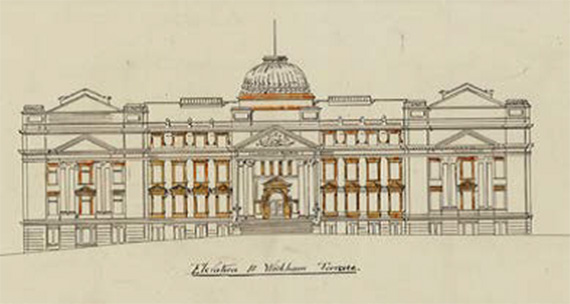

The idea to amalgamate two or more of the key cultural institutions in Brisbane was first proposed in 1889 when, the Queensland Department of Works held a competition for the design of a museum, art gallery and library. The competition was won by Charles McLay who proposed an imposing neoclassical building on a site in Wickham Terrace above Central Railway Station. Tenders were called for the project in March 1891 just as the government was facing a financial crisis and construction did not proceed.1

Plan of proposed Museum, Wickham Terrace by Charles McLay, 1891 / QSA Item ID108156

Plan of proposed Museum, Wickham Terrace by Charles McLay, 1891 / QSA Item ID108156

The idea of a cultural centre was again canvassed in 1927 when Raymond Nowland, architect and town planner, addressed the Town Planning Association of Queensland on the development and beautification of North Quay. Nowland proposed an ambitious scheme that involved removing unhappy structures fronting the Brisbane River and replacing them with an enlarged public library and an art gallery.2 Nothing eventuated but in 1934, Nowland re-visited the concept when working as a senior architect in the Department of Works. He was responsible for a scheme involving the redevelopment of Wickham Park fronting Turbot Street. Nowland proposed an ambitious project of three new public buildings: a dental hospital, art gallery and public library. The Courier Mail enthused about this ‘Civic Cultural Centre’, claiming that ‘at last a Queensland Government has been brought to recognise the State’s need of a national public library and a national art gallery worthy to bear those names, and to admit, also, some responsibility for repairing a long neglect of public cultural facilities in Queensland ‘s capital’.3

Wickham Park aerial view with proposed Dental Hospital, Art Gallery and Public Library, 1938 / QSA Item ID328720

Wickham Park aerial view with proposed Dental Hospital, Art Gallery and Public Library, 1938 / QSA Item ID328720

The Dental Hospital was built (completed in 1941) but not the art gallery or library. They would have to wait.

Brisbane Dental Hospital and College, June 1940 / Photograph: State Library of Queensland #54384

Brisbane Dental Hospital and College, June 1940 / Photograph: State Library of Queensland #54384

As Brisbane emerged from war-time restrictions on construction and public works projects in the later part of the 1940s, attention turned to major civic improvement schemes including beautifying the city and cultural facilities. In 1948 a scheme was proposed to move the Supreme Court buildings further east along George Street and create a square with an art gallery and new state library.4 In the following years, the Lord Mayor, Alderman Chandler, proposed a scheme of creating a wider tree-lined Albert Street from the City Hall to the Brisbane Botanic Gardens and that ‘the Art Gallery and Conservatorium should be housed near the gardens, as well as an opera house and library’.5 Again, these schemes remained but dreams.

The idea of locating the art gallery near the Botanic Gardens continued to be canvassed in the 1950s. To celebrate Queensland’s centenary in 1959, a proposal was submitted to Cabinet for the construction of a new gallery on a site near Government House at Gardens Point. The government responded enthusiastically and the Premier announced that a world-wide competition would be conducted for the design of the complex. The scheme quickly expanded into not only an art gallery but also a multi-purpose hall with seating for 1500 patrons for use for musical and dramatic presentations.6 This building was to be known as ‘Pioneers’ Hall’. The complex would be funded by a mix of public donations and government assistance. A committee was established comprising prominent identities associated with the arts and chaired by the Premier. Problems, however, soon emerged with the proposal. First, the Brisbane City Council announced in April 1959 that it was considering extending George Street through to the river for a new bridge at Gardens Point. Consequently, the area of land for the proposed Cultural Centre would be curtailed. Secondly, potential art-loving benefactors were concerned that their contributions would be devoted to the ‘Pioneers Hall’ and not a new art gallery. After the euphoria surrounding centenary celebrations had subsided in 1959, the scheme was eventually abandoned.

Another site in the Brisbane CBD soon emerged as the possible location for a Cultural Centre. The Brisbane Municipal Markets had operated from a site fronting Roma Street since 1881 and in 1960, the Market Authority decided to relocate to a new site at Rocklea. A range of uses for such a prime site were soon forthcoming, including a proposal by the Brisbane Women’s Club that it be reserved for a ‘Cultural Centre, together with a self-governing Art Gallery with adequate car parking facilities provided’.7 The State government commissioned the architectural firm, Bligh Jessup Bretnall and Partners, to prepare a master plan of the Roma Street precinct. The plan included a new State Gallery and Centre for Allied Arts located on the market site.8 While the government endorsed the plan and the location of an art gallery on Roma Street, the Brisbane City Council, who by this time had responsibility for the former market reserve, opted for a park.9 The council’s view was that a cultural centre was best suited in the Botanic Gardens as it had aspirations of developing a new botanic gardens at Mount Coot-tha.10 So like all previous proposals for a cultural centre, the Roma Street site had been abandoned by the end of 1968.

Within the Department of Works, however, the concept was still alive. The need for a new art gallery was a priority, but in late 1968, Roman Pavlyshyn, senior architect in the Works Department wrote to David Longland, the Director-General of the Works Department suggesting that the gallery ‘should be part of a complex of buildings dedicated to cultural purposes, including an opera and drama theatre and the Queensland Museum’.11 Longland pursued the idea with his Minister, Max Hodges, who then raised the matter with the Premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Hodges urged that a Select Committee be established to examine the need for a cultural centre, investigate the most appropriate site, and recommend methods of financing.12 The Premier then referred the matter to the Treasurer, Gordon Chalk. Although in general agreement with the concept, Chalk maintained that a new art gallery was a ‘matter of urgency’.13 Chalk was concerned that establishing such a committee would potentially delay for several years a new art gallery.

A NEW ART GALLERY

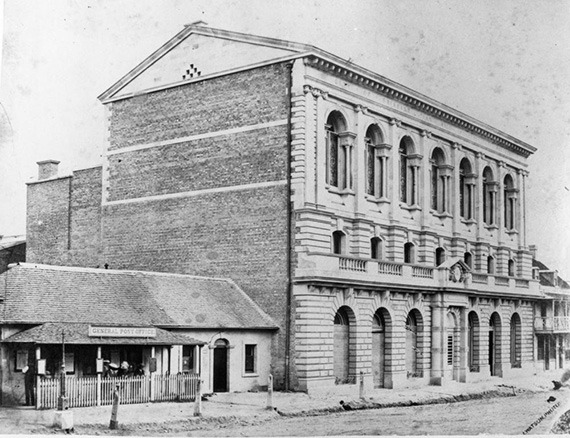

From its beginnings in 1895, the Queensland National Art Gallery had occupied a succession of spaces in various public buildings. From 1930, it had been accommodated in the former Concert Hall in the Exhibition Building on Gregory Terrace. These facilities were less than adequate and the Board of Trustees lobbied the Queensland government over an extended period for a purpose-built gallery. Finally in November 1968, the Board convinced the government to act.

The Queensland National Art Gallery opened in 1895 in the now demolished Brisbane Town Hall building in a large upper room placed at the disposal of the Trustees by the Municipal Council / Photograph: State Library of Queensland

The Queensland National Art Gallery opened in 1895 in the now demolished Brisbane Town Hall building in a large upper room placed at the disposal of the Trustees by the Municipal Council / Photograph: State Library of Queensland

In November 1968, prominent Australian art critic and historian Professor Bernard Smith visited the Gallery and told the Courier Mail that ‘one only has to be inside this gallery— even for 24 hours—to see that art in this institution is in a pretty sorry position’.14 The Chairman of the Board of Trustees, Sir Leon Trout, agreed. He asserted ‘the gallery is hopeless’ and publicly supported Smith’s claims that art in Queensland was ‘weedy and malnourished, and in a sense, suffering from cultural rickets’.15 These very public disparaging comments prompted an immediate response from the Government. Within two days, the acting Premier, Gordon Chalk, announced an investigation into the future of the Queensland Art Gallery.16 In January 1969, Cabinet approved the establishment of the Queensland Art Gallery Site Committee.17

SITE SELECTION AND PLANNING – A NEW ART GALLERY

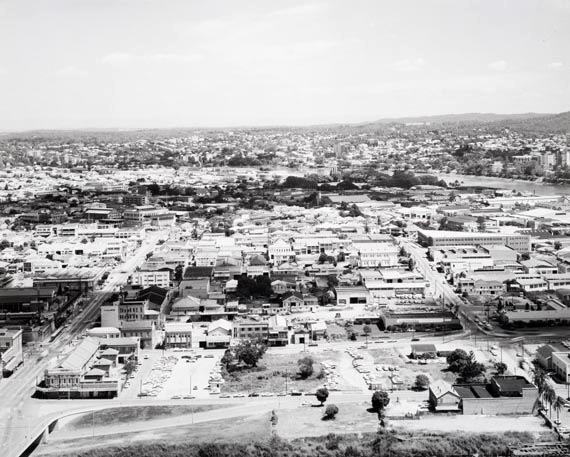

Overlooking South Brisbane, site of the future Queensland Art Gallery, 1950s

Overlooking South Brisbane, site of the future Queensland Art Gallery, 1950s

The committee examined twelve possible sites, and then reduced the number to three for more detailed consideration: Holy Name Cathedral site, Fortitude Valley; Brisbane City Council Transport depot, Coronation Drive; and Riverside Drive, South Brisbane.18 The committee agreed that the site at South Brisbane bounded by Melbourne and Grey Streets and the Brisbane River was the most suitable and in every way it appeared to be the most viable:

It was the Architecturally-preferred site;

The Brisbane City Council would be making a valuable contribution;

It was the site which would do most for the City of Brisbane;

There was potential for use of a similar block on the other side of Melbourne Street for cultural facilities.19

Some of the land was already in public ownership—State and Brisbane City Council—but a substantial number of privately owned allotments had to be acquired for the project. This became a lengthy process and some owners objected to the valuations.

Aerial view of South Brisbane c.1969

Aerial view of South Brisbane c.1969

Not until most of the land had been acquired did the government appoint a Steering Committee to provide a comprehensive report on the various requirements of the new Art Gallery, ‘sufficient to form the basis for the preparation of the design and for the development of planning and construction documents for the new building’.20 The committee was appointed in July 1971 and was chaired by Roman Pavlyshyn, Assistant Under Secretary in the Department of Works.21 Pavlyshyn was the principal author of the report and went on to play an influential role not only in the development of the Art Gallery but also the Cultural Centre.22

Site for the new Queensland Art Gallery, South Bank, 16 March 1976 / Collection: QAGOMA Research Library

Site for the new Queensland Art Gallery, South Bank, 16 March 1976 / Collection: QAGOMA Research Library

The report was comprehensive and included recommendations on space requirements, costs, method of planning and construction and a detailed planning brief. The committee concluded a building of 140 000 sq feet (13 000 m²) at an estimated cost of $4.5 million was required.23 The report alluded to the possibility that the site could be used to accommodate other cultural activities. The committee recommended that a two-stage architectural competition be held to select an architect for the design of the new gallery.

The planning brief was concise but thorough. It emphasised ‘that the gallery should be an active and human place to which the visiting public will be attracted to participate in the enjoyment of the facilities provided by the gallery’. The brief, also noted, rather presciently, ’that it is possible that the future activities and requirements of the gallery may call for facilities which cannot be foreseen at present’.24 Significantly, the Planning Brief not only addressed issues such as functional requirements, the site and town planning issues, but also focused on desired design criteria. They included the following principles:

It is desirable that the building itself should be of the highest possible standard of architectural design. This does not mean that it should be either monumental or pretentious in character. It should be a building of its time incorporating the best techniques and materials available within the economic limits of the project.

A public gallery is a symbol of artistic and cultural development. It should have human qualities and attractions of a kind which encourage people to visit the collection, and to take pleasure in being in a place where the artistic achievements of the community are effectively but unostentatiously displayed for their enjoyment.

More informality should be the keynote which should also take advantage of the subtropical climatic conditions which prevail in Brisbane. The site on the Brisbane River selected for the building, suggests that it should be outward looking to take advantage of the views of the tree-clad hills which form the setting for the city of Brisbane. The gallery will be seen to great advantage in views from across the river and from other vantage points in the city.

The fine, Mediterranean-like quality of the Brisbane climate is such that a building, light in colour, but carefully modelled to give interesting effects of light and shade might be most suitable…

The landscaping proposals for the site should be an integral part of the total design. Courts for the display of sculpture and shaded areas for rest and relaxation should be included. The paving, lighting and furnishing of these areas to the relationship of the building and its setting to the river are all matters of particular design importance.25

The design principles also addressed issues of space, volume and scale. The planning brief stressed that the ‘relationship of the exhibition spaces or galleries to each other is of great importance’ and that ‘areas linking the display galleries should be attractively arranged, where possible, with views outside the building to provide contrast and to avoid museum fatigue’. The brief highlighted the importance of access and circulation, stressing that ‘it is of the greatest importance that a major public building of this kind should have an appropriate address’ and that ‘the main public entrance should be clearly identifiable and attractively designed’.26

The planning brief submitted in March 1972 was a key document in the successful design and development of the art gallery, due to its clarity, vision and understanding of the context and requirements for a modern art gallery. It was accepted by Cabinet and approval given to proceed with the project.27

THE COMPETITION

As recommended by the Steering Committee, a two-stage design competition was conducted. The assessors panel consisted of Sir Leon Trout, Chairman of the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees, Roman Pavlyshyn, Assistant Under Secretary, Department of Works, and Stanley Marquis- Kyle, representing the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. The first stage was to invite ten firms on the register for Queensland government work with the Works Department to participate in the competition. These firms were all well respected Brisbane-based architectural firms.28 The first stage closed in November 1972 and the names of the three firms proceeding to the second stage were announced in the following month. They were:

Bligh Jessup Bretnall and Partners; Robin Gibson and Partners; and Lund, Hutton, Newell Paulsen. The second stage closed on 1 March 1973 and the winner of the competition, Robin Gibson and Partners, announced on 16 April 1973.29 The assessors concluded that the ‘winning design exhibits great clarity and simplicity of concept and relates admirably to the environment and site’.30 Gibson later commented to the Steering Committee for the new Art Gallery that in ‘developing the design to final completion it was necessary to keep in mind the original basic design philosophy’ that had been articulated in the Planning Brief.31 Gibson began working on the detailed design for the art gallery but the program was delayed when the question of a cultural centre re-surfaced as a definite project.

RE-EMERGENCE OF A CULTURAL CENTRE SCHEME

While the art gallery project had been the focus of the government’s attention, the plans for a cultural centre were not entirely abandoned. In March 1971, Allan Fletcher, Minister for Education and Cultural Activities submitted a proposal to Cabinet for the acquisition of two blocks at South Brisbane for the State Library and Museum. Fletcher had the support of the Brisbane City Council, but the proposal was rejected.32 By early 1974, the emergence of a range of issues coalesced to bring the need for a cultural centre at South Brisbane to the government’s attention.

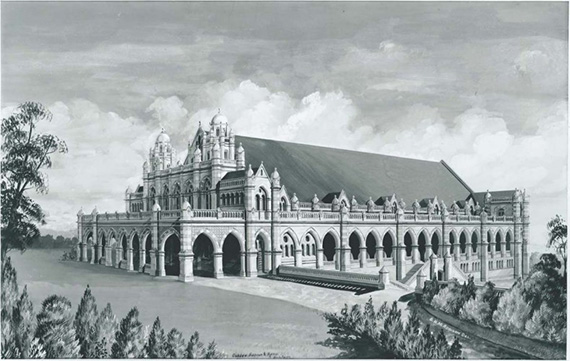

G H M Addison, Australia 1858-1922 / (Architect’s drawing of Exhibition Building, Gregory Terrace) c.1890 / Pen, ink and gouache on light-brown heavy smooth paper / Gift of Herbert S. Macdonald 1958 / Collection: QAGOMA Research Library

G H M Addison, Australia 1858-1922 / (Architect’s drawing of Exhibition Building, Gregory Terrace) c.1890 / Pen, ink and gouache on light-brown heavy smooth paper / Gift of Herbert S. Macdonald 1958 / Collection: QAGOMA Research Library

Just as much as a new art gallery was a priority, it had become increasingly clear that a new museum, state library and a state-of-the-art performing arts centre was also needed. In 1973, the Board of Trustees of the Queensland Museum had commissioned a feasibility study on the re-development of the Queensland Museum as the conditions in the Exhibition Building were less than adequate.33 The study investigated a range of sites and recommended a site within Albert Park with a building of 216 000 sq feet (19 565 m²) floor area.34 This study provided a compelling argument for a new museum. Similarly, the State Library, occupying a building erected in 1879 with extensions in 1959, was in urgent need of additional space, not only for the collections but also for users. The Works Department commissioned Robin Gibson and Partners to undertake a feasibility study to demonstrate how the existing building in William Street could be extended.35

Although the state government did not own or operate a major performing arts venue, the sale of Her Majesty’s Theatre in 1973 was cause for grave concern about the future of the performing arts in Brisbane. The building had been the main venue for opera, ballet and dramatic performances since 1888. The new owners intended to demolish the building and re-develop the site.36

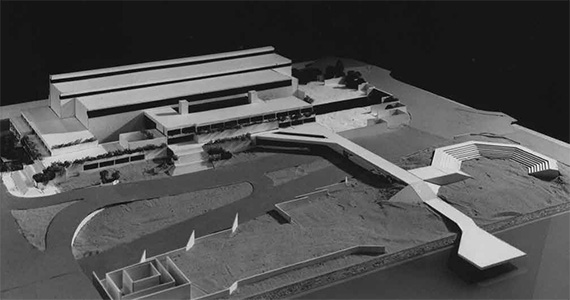

Model, Queensland Art Gallery, 1973 / Photograph: Richard Stringer

Model, Queensland Art Gallery, 1973 / Photograph: Richard Stringer

In February 1974, Alan Fletcher the Minister for Education and Cultural Activities, submitted to Cabinet a proposal for the acquisition of a site for a performing arts centre. Unlike the previous occasion when he sought Cabinet approval for land for a new library and museum, on this occasion approval in principle was given to investigate the question.37 The suggested site was at South Brisbane to the north-west of the Art Gallery site. Two months later, the Premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen announced that ‘Brisbane may get an Arts Centre’. In a media release he said the centre could incorporate the Queensland Art Gallery, the Queensland Museum, a concert hall and facilities for live theatre, ballet and other performing arts. The Premier said he had asked the Coordinator General to undertake a feasibility study into the planning and financing of the centre.38

The member for Chatsworth, WD Hewitt, expressed his concerns in a speech in the Legislative Assembly in September 1974. He commented:

It is obvious that Brisbane needs a cultural centre and that urgent attention must be given to this matter…Recognising that Her Majesty’s Theatre is presently under the threat of the wrecker’s hammer, I submit that some action must be taken to fill the vacuum that its closure would cause.39

Hewitt surprisingly would not wait long for an answer, the Treasurer, Gordon Chalk, had engaged Robin Gibson and Partners to assist in the development of a brief and prepare sketch plans and a physical scale model Cultural Centre at South Brisbane.

Model of the Cultural Centre prepared in 1974 / Photograph: Richard Stringer QPACA

Model of the Cultural Centre prepared in 1974 / Photograph: Richard Stringer QPACA

Chalk announced his presented scheme to the public on 14 November 1974 as part of the Liberal Party policy launch for the State election in the following month. Chalk said the complex would comprise a museum equal to any in Australia; an outstanding art gallery; a performing arts centre; a new public library; and restaurant’.40 On the day of the announcement, Chalk unveiled in his office a model of the complex prepared by Robin Gibson and Partners. The Courier Mail declared that leading figures in the arts community were unanimous that this was an ‘imaginative and exciting project.’41

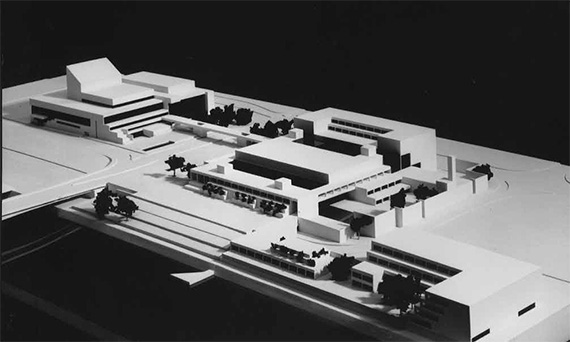

Cultural Centre model, 1975/ Photograph: Richard Stringer QPACA

Cultural Centre model, 1975/ Photograph: Richard Stringer QPACA

The initial plans and scale model of the Cultural Centre differed in some key elements from what ultimately eventuated on the site. The general location of the principal four buildings was as finally determined. However, the 1974 model was distinguished by triangular and trapezoidal building forms, unlike the later simpler rectangular expressions. The gallery was diagonally aligned to face Melbourne Street and the river and stepped to a plaza. An overhead walkway over Melbourne Street linked the two parts of site.

Model of the Cultural Centre, c. 1977 with more detail than

Model of the Cultural Centre, c. 1977 with more detail than

shown in the 1975 model / Photograph: Richard Stringer QPACA

Chalk presented his proposal for a Cultural Centre at South Brisbane to Cabinet on 18 November 1974.42 The submission outlined the current needs of the various cultural institutions and the advantages of an integrated and coordinated complex. Co-locating an art gallery, museum, library and performing arts centre would mean the sharing of car parking facilities, restaurants, mechanical services and some staff resources. In addition, the close proximity of the institutions had the ‘potential for much needed interaction’. The total cost for the Cultural Centre including land acquisition, car parking and site works was $45.4 million.43

Aerial view of the Cultural Centre, 1978

Aerial view of the Cultural Centre, 1978

Cabinet agreed to the project and the following immediate action:

(i) Acquire the necessary land as urgently as possible

(ii) Establish a body for the Performing Arts Centre

(iii) Establish a coordinating and planning management body for the overall cultural complex.

The question remained—would this be the scheme that came to fruition? The Courier Mail editorialised that ‘Queenslanders understandably have become cynical after 79 years of promises…[and] there is nothing like an election to get things moving’.44 But in this case they did.

Queensland Cultural Centre featuring the Queensland Art Gallery, 1982

Queensland Cultural Centre featuring the Queensland Art Gallery, 1982

This is an extract from the Queensland Cultural Centre Conservation Management Plan (published 2017), prepared by Conrad Gargett in association with Thom Blake, Historian and heritage consultant. Thom Blake researched and wrote the chapters on the history of the Cultural Centre and revised statement of significance. The individual building’s architecture, the site’s setting, landscape and fabric were investigated by Luke Pendergast with principal support by Robert Riddel. Alan Kirkwood and Peter Roy assisted with advice on the design approach and history of the planning and construction of the Cultural Centre.

Endnotes

1 Brisbane Courier, 2 October 1889, 7 November 1889, 25 March 1891.

2 Brisbane Courier, 27 February 1927.

3 Courier Mail, 13 November 1934.

4 The Sunday Mail, 14 March 1948.

5 The Sunday Mail, 30 October 1949.

6 Australian Institute of Architects, ‘Application for entry of a State Heritage Place, Queensland Cultural Centre,4 August 2014′ww, p. 22.

7 Proposed use of former Municipal Markets Reserve, 15 January 1969, QSA Item ID961644.

8 Bligh Jessup Bretnall and Partners, Plan for Redevelopment of Roma Street Area City of Brisbane, Department of the Co-ordinator General of Public Works, Brisbane, 1967; Courier Mail, 11 January 1967.

9 Courier Mail, 16 November 1968.

10 Australian Institute of Architects, Application, p. 23.

11 Pavlyshyn Memoirs.

12 Minister for Works and Housing to Hon. Joh Bjelke-Petersen, 10 January 1969, QSA Item ID957244.

13 Gordon Chalk to Hon. Joh Bjelke-Petersen, 21 February 1969, QSA Item ID957244.

14 Courier Mail, 14 November 1968.

15 Ibid.

16 Courier Mail, 16 November 1968.

17 Cabinet decision No 12536, 14 January 1969, QSA Item ID541022.

18 Queensland Art Gallery Site Committee, ‘Proposed Art Centre Site Investigation’, March 1969, QSA Item ID 961664. The initial sites considered were: Exhibition building site; Albert Park, Old Markets Roma Street, Botanic Gardens, Central Railway Station, block bounded by Wharf, Adelaide and Ann Streets, Holy Name Cathedral, Isles Lane, Treasury Building, Lower Edward Street, Riverside Drive near Victoria Bridge, Brisbane City Council Transport depot Coronation Drive.

19 Ibid., p. 2.

20 New Queensland Art Gallery Steering Committee, ‘Queensland Art Gallery Report’, March 1972, QSA Item ID961664.

21 The other committee members were: AE Guymer, Director General of Education; Sir Leon Trout, Chairman of the Board of Trustees; AJ Stratigos, Deputy Chairman of the Board of Trustees, James Weineke, Director of the Queensland Art Gallery, Professor GE Roberts, Professor of Architecture, University of Queensland; Peter Prystupa, Supervising Architect, Department of Works. (New Queensland Art Gallery Steering Committee, ’Queensland Art Gallery Report’, March 1972, QSA Item ID961664. p. 2).

22 Although Pavlyshyn is not specifically identified as the author, it is clear from other reports he wrote and also the minutes of the Steering Committee on 26 October 1971, that he was responsible for drafting the text on which the committee then provided comment (Minutes of Steering Committee, 26 October 1917, QSA Item ID601046).

23 Land acquisition, site works and a car park were estimated at $2.5 million, Ibid, p. 6.

24 New Queensland Art Gallery Steering Committee, ‘Queensland Art Gallery Report’, March 1972, QSA Item ID961664, Appendix C, p. 4.

25 Ibid., pp. 7-8.

26 Ibid., p. 9.

27 Cabinet decision No 16829, 21 March 1969 QSA Item ID601046.

28 These firms were: James Birrell and Partners; Bligh, Jessup, Bretnall and Partners; Consortium of Codd, Hopgood and Associates, HJ Parkinson and Associates, Blair M Wilson; Conrad, Gargett and Partners; Cullen, Fagg, Hargraves, Mooney and Cullen; Fulton, Collin, Boys, Gilmour, Trotter and Partners; Robin Gibson and Partners; Hall, Phillips and Wilson; Lund, Hutton, Newell, Paulsen;and Prangley and Crofts (Under Secretary, Department of Works, 15 August 1972, QSA Item ID601046).

29 Courier Mail, 17 April 1973.

30 The Australian, 17 April 1973.

31 Minutes of the Steering Committee for the new Queensland Art Gallery, 10 January 1974, QSA Item ID601046.

32 Architects Institute of Australia, Submission, p. 24.

33 Fulton, Collin, Boys, Gilmour, Trotter & Partners, Feasibility Survey Re-Development of Queensland Museum, 1973, QSA Item ID315623.

34 A total of 17 sites were considered and three short-listed: Albert Park, Woolloongabba Rail Yards and Toowong East (currently bush-land between Old Mount Coot-tha Road and Birdwood Terrace).

35 Plans, State Public Library feasibility study, QSA Item ID121879.

36 Courier Mail, 28 June 1973. Her Majesty’s Theatre was finally demolished in 1983 and the Hilton Hotel and Wintergarden Shopping Centre built on the site.

37 Cabinet decision No 20057, 5 February 1974, QSA Item ID569765.

38 Media release, 28 April 1974, QSA Item ID569765.

39 Queensland Parliamentary Debates, 11 September 1974, p. 720.

40 Courier Mail, 15 November 1974.

41 Ibid.

42 Cabinet decision No 21481, QSA Item ID541022.

43 Ibid.

44 Courier Mail, 16 November 1974.

Copyright © 2008

This feed is for personal, non-commercial use only.

The use of this feed on other websites breaches copyright. If this content is not in your news reader, it makes the page you are viewing an infringement of the copyright. (Digital Fingerprint:

)