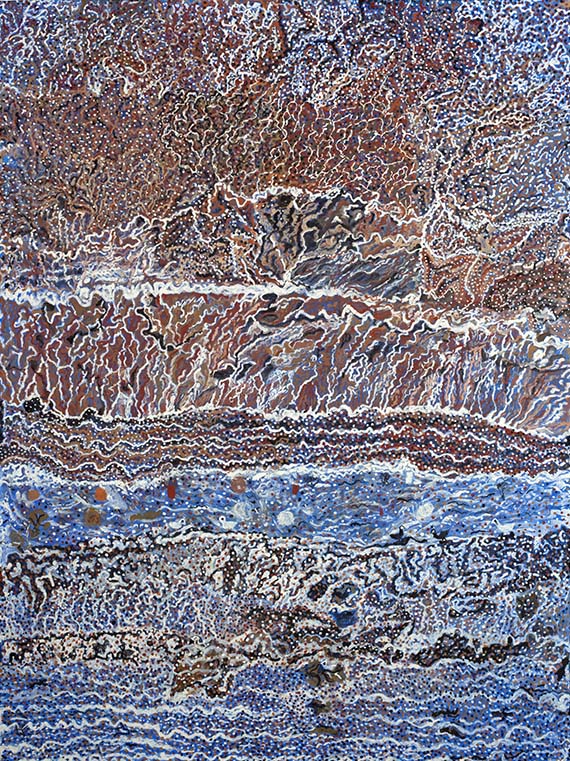

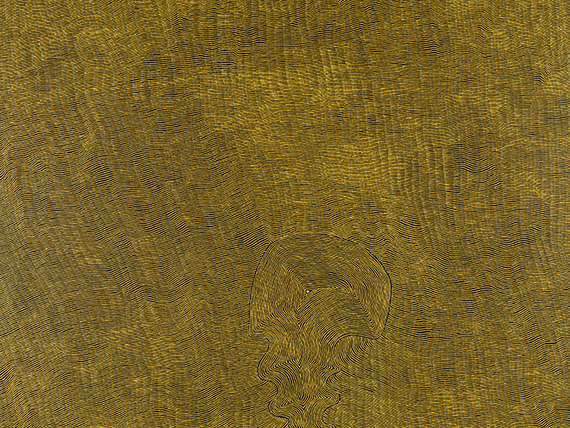

Bangaliwuy Marrawungu / Bunhangura towards Dhuwalkitj 1947 / Lumber crayon on butchers’ paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Bangaliwuy Marrawungu / Bunhangura towards Dhuwalkitj 1947 / Lumber crayon on butchers’ paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

For the first time, a selection of 81 of a collection of 365 vibrant, colourful crayon drawings made by a group of senior Aboriginal leaders and bark painters in Yirrkala, north-east Arnhem Land, are the focus of an exhibition created by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, in collaboration with Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre at Yirrkala and the Berndt Museum at the University of Western Australia in Perth. Here, exhibition curator Cara Pinchbeck writes on these extraordinary works and the history behind them.

The Yirrkala crayon drawings are a unique collection of artworks, stunning in their visual strength and impact. They are also an unrivalled document of Yolngu knowledge and law. The works were made by the senior leaders of the Yirrkala community in 1947 through their collaboration with the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt. The Berndts had travelled to Yirrkala to undertake research, arriving in late 1946, and as part of their work asked artists to produce paintings in natural pigments on bark. In the first two months of their research they collected over 200 bark paintings. Their concern that these works would be destroyed when transported out of Yirrkala led Ronald Berndt to request rolls of butchers’ paper and boxes of coloured crayons from his father in Adelaide. This method of recording Indigenous knowledge had been used by other anthropologists and allowed an immediacy not replicated in other mediums, in addition to being easily transportable.

This new art form was embraced by the artists working at Yirrkala and over the next five months they created 365 crayon drawings that the Berndts then painstakingly documented. The works are distinct in the brilliant colour palette used and the complexity of the information contained within them. The collection evidences the amazing things that can be achieved through collaboration, mutual respect and understanding. These attributes have been central to the development of this exhibition, with people from all four corners of the continent working together to ensure that these works are accessible and the exceptional artists who created them are afforded the recognition they deserve.

Mowarra Ganambarr / Djang’kawu created waterhole on Dätiwuy estate 1947 / Lumber crayon and graphite on butchers paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Mowarra Ganambarr / Djang’kawu created waterhole on Dätiwuy estate 1947 / Lumber crayon and graphite on butchers paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

The crayon drawings are now held by the Berndt Museum of Anthropology of the University of Western Australia, Perth, which is a partner in this project, along with Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, the art centre that services the artists of Yirrkala today. A small number of the drawings have been included in the Berndt Museum exhibition ‘Djalkiri Wanga: the Land is my Foundation’ (1995) and the National Museum of Australia’s ‘Yalangbara: Art of the Djang’kawu’ (2010–12)1. However, ‘Yirrkala Drawings’ is the first major exhibition to include a significant number of the works, with the accompanying catalogue publishing the entire collection. The descendants of the artists who worked with Ronald Berndt have actively sought an exhibition of this nature for some time, so that their fathers and grandfathers can be known and the extent of what they achieved in working with the Berndts can be fully appreciated.

Although much is known of Ronald and Catherine Berndt and their work, far less is known of the majority of the artists with whom they collaborated. Many of these men are among the most important bark painters of the twentieth century, exceptional artists who were also cultural leaders and social negotiators, and deserve to be recognised as important figures in the history of this country.

Wonggu Mununggurr / Fish trap at Wandawuy 1947 / Lumber crayon on butchers’ paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Wonggu Mununggurr / Fish trap at Wandawuy 1947 / Lumber crayon on butchers’ paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

When Wonggu Mununggurr began working with the Berndts during their trip to Yirrkala in 1946–47, he was a cultural leader who had led an extraordinary life. That Wonggu decided to collaborate with them, and comprehensively document the complexities of Yolngu culture and law in the brilliant works that we see in this exhibition, highlights his generosity and desire to share knowledge as a form of cross-cultural collaboration. To some, this may seem a surprising thing to do, but when considering Wonggu’s life experiences we see that they are marked by engagements with outsiders, at times complex but predominantly based on generosity and cooperation. Working with the Berndts was just another of his partnerships. Of course, Wonggu was not the only artist to work with the Berndts, but he was certainly the most productive, creating an amazing 84 of the 365 works that form the Yirrkala crayon drawing collection from 1947. In considering Wonggu’s life, we are able to gain an insight into the lives of many of the artists who worked with the Berndts and events that preceded this seminal collection of drawings.

Born in the early to mid 1880s, Wonggu grew up on country, travelling to various camps with the changing seasons. During his early years, Macassan traders visited annually and lived with the Yolngu for several months. These important ties that had spanned centuries were severed when Wonggu was in his early twenties and the government introduced license fees, effectively banning such visits. By August 1932, Wonggu had allowed Fredrick Gray to camp on his country at Caledon Bay and establish a trepang (sea cucumber) processing plant. Wonggu and his family worked for Gray, utilising their extensive skills and continuing the long history in the trade of their natural resources.

In 1934, Wonggu was described in Brisbane’s Courier-Mail as the ‘King of the Balamumu’ and he and his sons as the ‘Black Gangsters of Caledon Bay’. Such reports were in relation to a number of murders in the region with three of Wonggu’s sons, Maw’, Natjialma and Dhangatji Mununggurr, being convicted of the murder of five Japanese trepangers after voluntarily going to Darwin for what was to be a fraught trial. During this time Wonggu began working with Donald Thomson who had been travelling throughout north-eastern Arnhem Land, with the government’s support, to resolve tensions in the area. Given his reputation, Wonggu was key to Thomson’s engagements with the Yolngu and they developed a close association and friendship that is apparent in Thomson’s engaging photographs and writing:

Wonggu proved to be a man of remarkable intelligence . . . frank and completely fearless, and each day my respect increased for this gallant warrior . . . the grand old man of the people of Caledon Bay.2

Wonggu was a leader of the people of Caledon Bay, the Djapu clan, and he travelled extensively throughout his country with his extended family, reported to include 20 wives and 60 children, before settling in the Methodist Mission at Yirrkala in 1937–38. This distinct change to mission life brought Wonggu into closer contact with the numerous clans of the region who were now all living on Rirratjingu clan country. In 1942, Wonggu worked with Thomson again, providing scouts and guides to Thomson’s Special Reconnaissance Unit, who defended the region against the Japanese as part of operations for World War Two, with six of Wonggu’s sons being members of the detachment.

In each of these engagements we see Wonggu’s desire to work collaboratively, which he continued in working with the Berndts when they arrived at Yirrkala in late 1946. The Berndts were interested in Wonggu’s life and immense cultural knowledge and provided him with a forum for making his inheritance known on terms that were appropriate and appreciated. Wonggu was by no means alone in this endeavour. Twenty-six of his peers from various clan groups were provided with the same forum and chose to work with the Berndts, enthusiastically responding to the desire for them to provide detailed images of country, accompanied by extensive documentation. The result was astounding and Berndt considered this body of work to be his greatest accomplishment.

The sheer size of the collection is staggering, as is the grand scale of the individual works and their vibrant colouration. However, the overriding strength of these drawings lies in the mastery of the artists in working with the new medium of crayon on paper. Although the process of drawing on paper is vastly different from painting in natural pigments on bark, the artists seamlessly translated their inherited clan designs to this new medium. While this highlights the willingness of the artists to try new things, it also shows the strength of visual language that is inherent in Yolngu art. When the use of crayon did not provide the desired effect required by some artists, pencil was introduced to achieve the precise line work and fine detail that is inherent to bark painting. It is thought that the pencil, and the occasional chalk to be found in the works, may have come from the Yirrkala Mission School.

The knowledge embedded within the works is phenomenal and their complexity shows that the artists knew exactly what they were doing — documenting their title deeds to land, laying down details of Yolngu law and providing meticulous information on the ancestors that are intimately connected to country and inform being in the present. The artists were explaining their world and worldview to outsiders. Through the works we learn the intricacies of culture, clan relationships and connection to country, from the land to freshwater, saltwater and the sky.

An important aspect of this project has been providing the artists’ families with access to the artworks and documentation of their fathers and grandfathers and allowing people to openly comment on these. Through this process details have been corrected, new information has come to light and discussion has been provoked about the importance of these men and the significance of what they did. These insights have been captured in the filmed interviews that feature in the exhibition catalogue, as well as short films within the exhibition space. The interviews allow people to speak of their own family, the artworks and the subjects depicted in their own terms. This has added an additional layer of knowledge and meaning to the works, while also bringing to light little known aspects of Australian history.

Yirrkala remains an important centre of artistic excellence, with many of the descendants of the artists who created the crayon drawings being artists of national and international renown today. Working through Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, these artists produce extraordinary works that both honour and offer innovation within the visual language refined by their fathers and grandfathers, as seen in the stunning larrakitj (hollow logs) that will be displayed in this exhibition.

Wonggu Mununggurr / Fish trap at Wandawuy 1947 / Lumber crayon on butchers paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Wonggu Mununggurr / Fish trap at Wandawuy 1947 / Lumber crayon on butchers paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Wonggu Mununggurr and his peers have left an amazing legacy through their landmark artworks, the comprehensive documentation of Yolngu knowledge that accompanies these and the artistic skills they have handed on to their descendants. Ronald and Catherine Berndt were keenly aware of what these men had created:

Our deep sense of gratitude to the Arnhem Landers themselves, particularly those at Yirrkala . . . cannot be expressed in mere words. Perhaps one day . . . these people will read with interest this history of these people’s contact with alien groups. In this way they will receive some compensation and, in some slight degree, our debt to them will be honoured.3

It is our hope that this exhibition goes some way in honouring this debt, in giving back to the Yirrkala community, bestowing the individual artists with the recognition they deserve and providing access to the artistic and cultural inheritance the artists of the Yirrkala crayon drawings have left us all.

Cara Pinchbeck is Curator, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales, and exhibition curator of ‘Yirrkala Drawings’.

Mawalan Marika and Wandjuk Marika / Yalangbara sandhills and goanna holes 1947 / Lumber crayon and graphite on butchers paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Mawalan Marika and Wandjuk Marika / Yalangbara sandhills and goanna holes 1947 / Lumber crayon and graphite on butchers paper / Ronald M and Catherine H Berndt Collection, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

Endnotes

1 ‘Yalangbara: Art of the Djang’kawu’ was a touring exhibition presented by the National Museum of Australia, developed by the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in partnership with the Marika family, and supported by the Northern Territory Government.

2 Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2003.

3 Foreword, Arnhem Land: Its History and its People, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1954. This is an edited excerpt of an article originally published in the November 2013 edition of Look, the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s magazine for members. Reproduced with the kind permission of Cara Pinchbeck and Jill Sykes, Editor, Look magazine. ‘Yirrkala Drawings’ is at QAG from 12 April to 13 July 2014. The Gallery holds bark paintings by some of the original Yirrkala artists, including Mawalan and Wandjuk Marika, Munggurrawuy Yunupingu and Mowarra Ganambarr, and larrakitj, bark paintings and prints by their descendants, including Dhuwarrwarr Marika, Wanyubi Marika, Gulumbu Yunupingu and Gunybi Ganambarr. A selection of their contemporary works will accompany the 1946 drawings in the exhibition.

‘Yirrkala Drawings’ is at QAG until 13 July 2014. The Gallery holds bark paintings by some of the original Yirrkala artists, including Mawalan and Wandjuk Marika, Munggurrawuy Yunupingu and Mowarra Ganambarr, and larrakitj, bark paintings and prints by their descendants, including Dhuwarrwarr Marika, Wanyubi Marika, Gulumbu Yunupingu and Gunybi Ganambarr. A selection of their contemporary works will accompany the 1946 drawings in the exhibition.

Dynamic, vivid and unlike any other Indigenous Australian artworks, these magnificent crayon drawings by senior Aboriginal leaders and bark painters of Yirrkala in north-east Arnhem Land are showcased in Yirrkala Drawings, the first comprehensive publication on the subject. Accompanied by insightful essays and interviews with the artists’ descendants, this book reveals the enduring power of this land and its people. The publication is available from the QAGOMA Store and online.

Copyright © 2008

This feed is for personal, non-commercial use only.

The use of this feed on other websites breaches copyright. If this content is not in your news reader, it makes the page you are viewing an infringement of the copyright. (Digital Fingerprint:

)