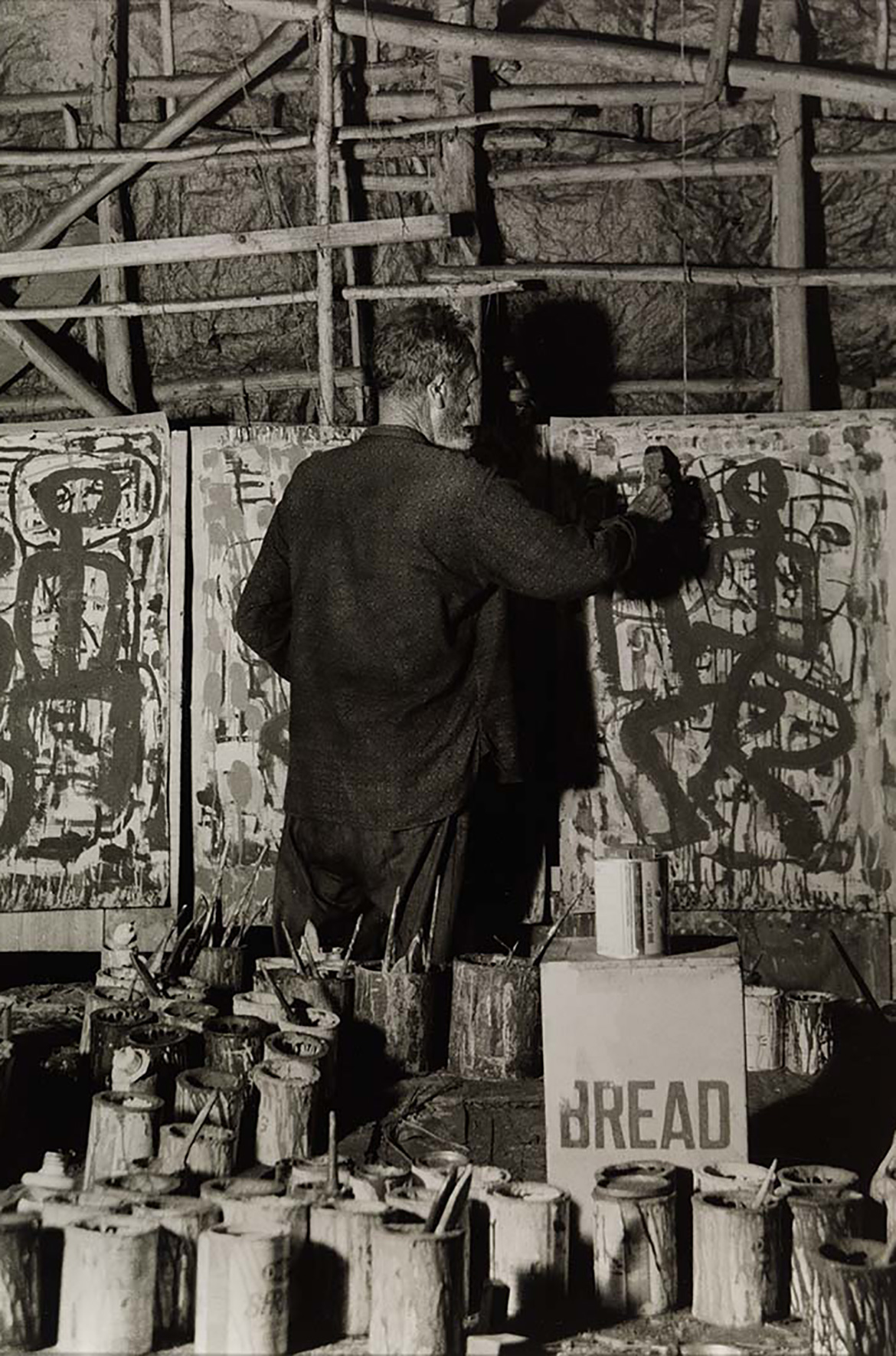

Dick Roughsey is well known to many Australians for his vividly illustrated children’s books The Rainbow Serpent and The Giant Devil Dingo – Jennifer Isaacs explores his life and work and offers her personal recollections of the artist, from his upbringing on Mornington Island to his pivotal role in the early years of the Australia Council.

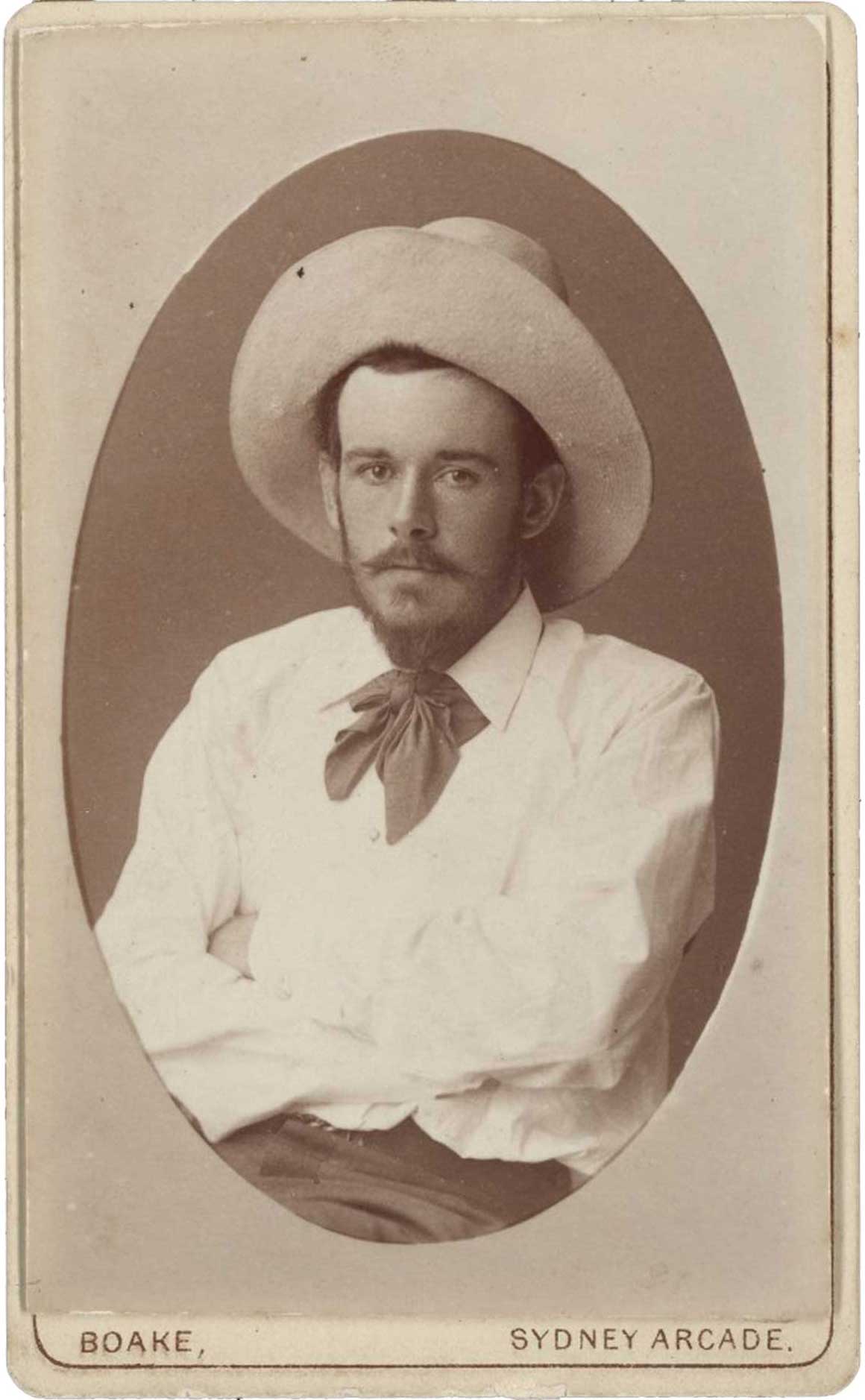

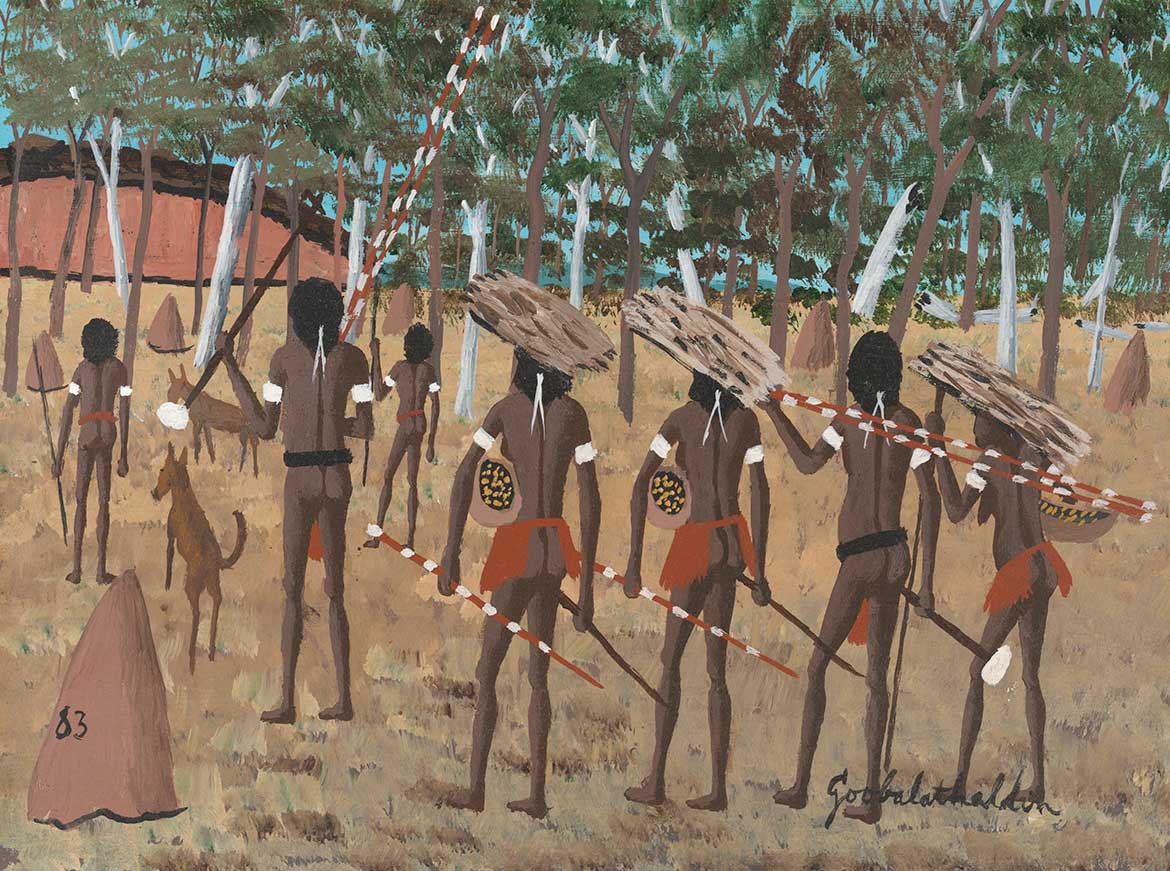

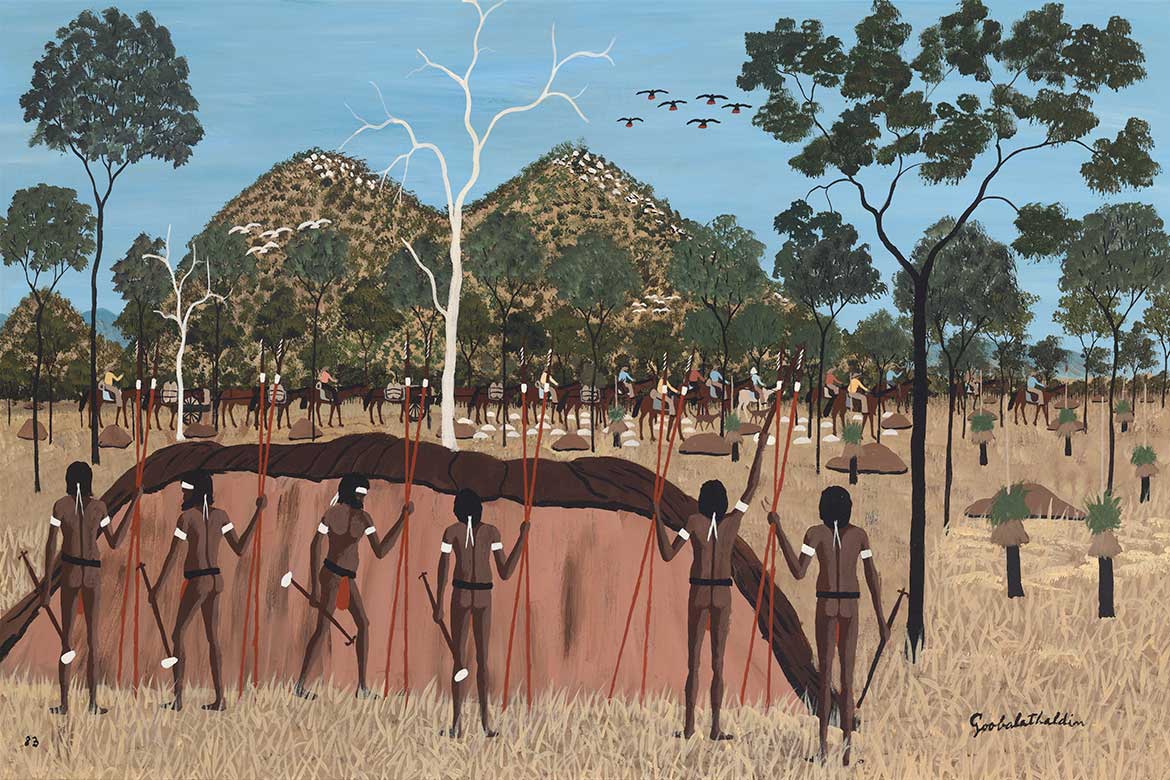

Dick Roughsey, also known as Goobalathaldin, was a Lardil artist from Mornington Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria. While his artistic practice had its origins in traditional bark painting, he later transitioned into modern paintings in oil and acrylic and became well known for his illustrated children’s books, winning the Children’s Book of the Year award twice during the late 1970s. His writing and art made him a pioneer cultural educator, and his book Moon and Rainbow (1971) was the first autobiography by an Indigenous Australian. He was appointed OBE in 1978.

Stay Connected: Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog

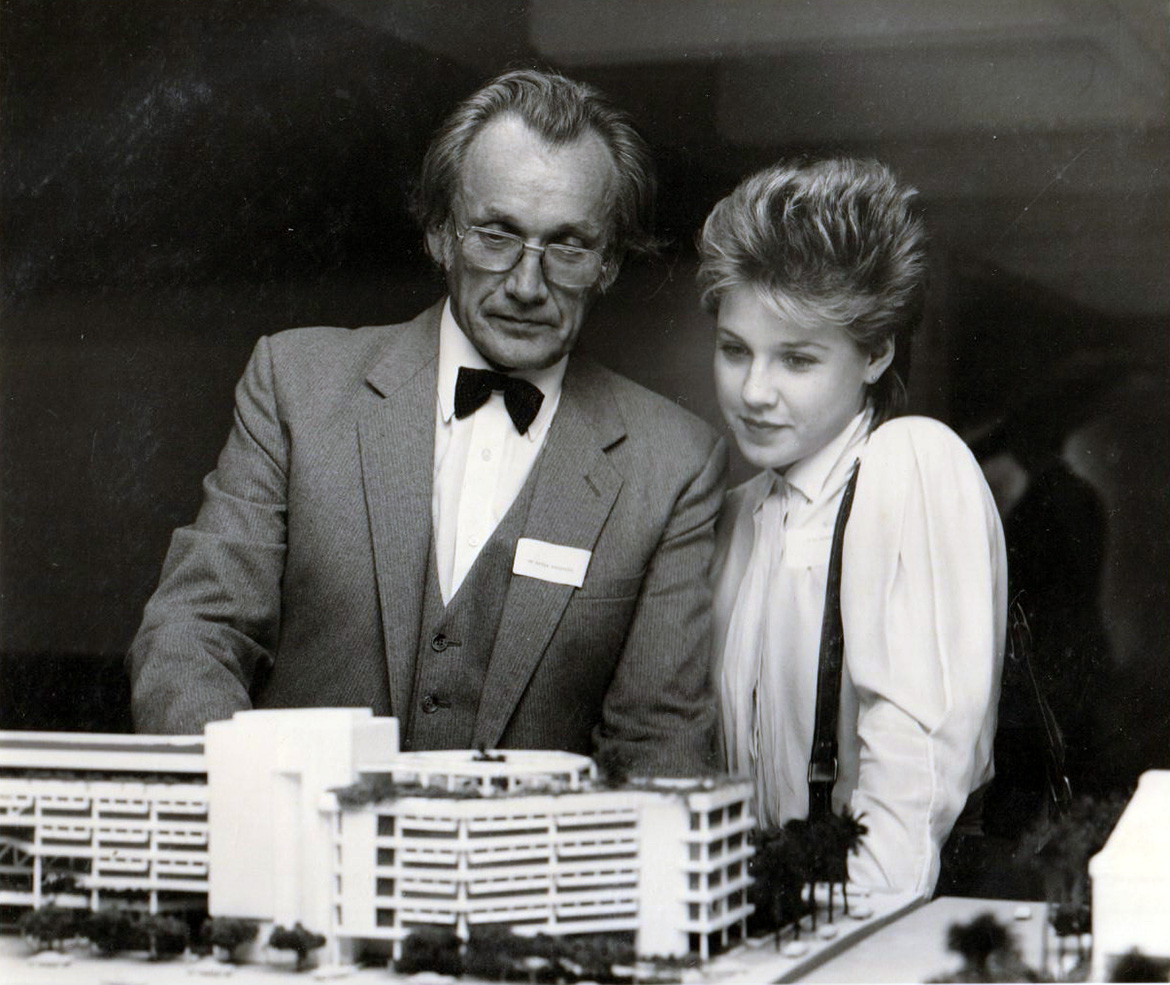

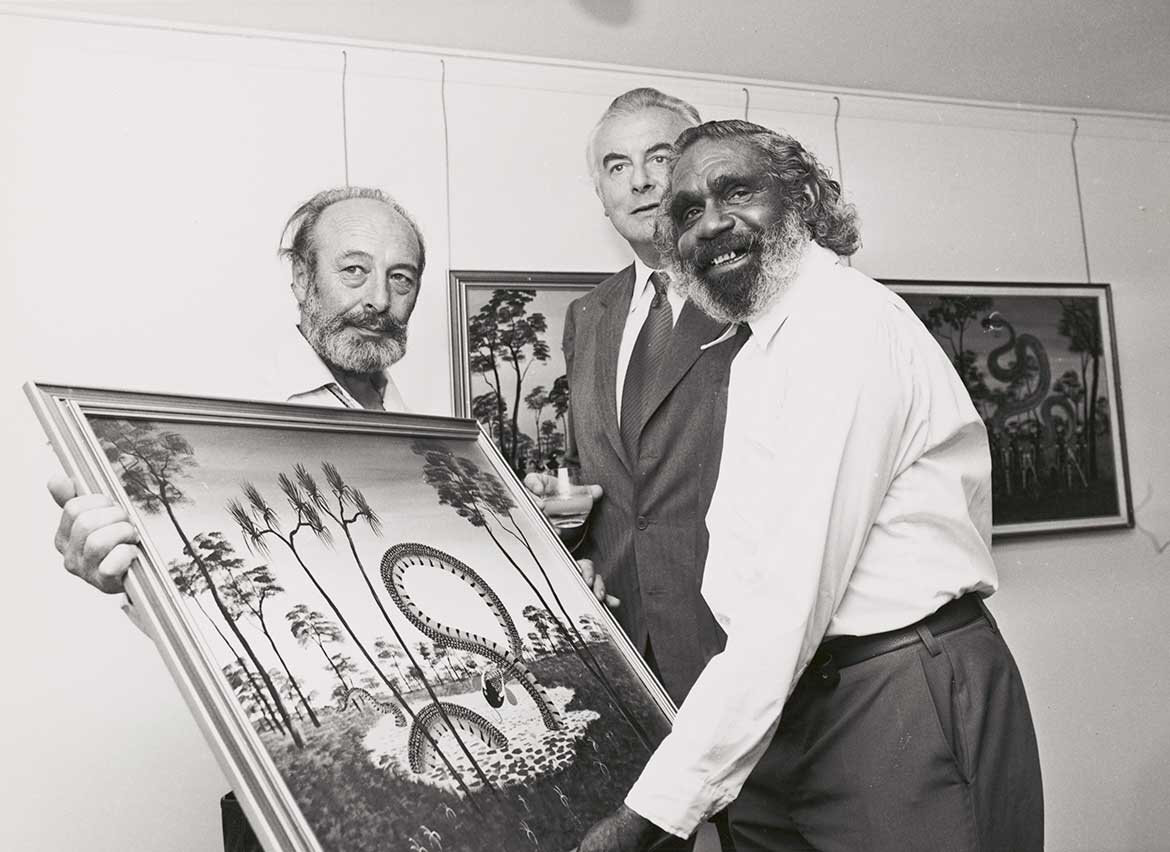

I first met Dick in 1970, stepping out of a lift with his friend and fellow painter, Percy Trezise. Percy was an airline pilot, historian and documenter of Aboriginal rock art, and together he and Dick spent many years locating cave painting sites near Laura in Cape York, which Percy mapped with meticulous scale drawings. On this occasion they were arriving to present plans for the preservation of these cave paintings at a meeting of the Aboriginal Advisory Committee of the Australia Council for the Arts, chaired by Dr HC ‘Nugget’ Coombs. Following the successful 1967 Referendum, the Australian Government was looking to encourage and stimulate the arts of Aboriginal Australians through a range of policy initiatives designed to support all areas of cultural practice; this committee included the most outstanding Indigenous leaders in the arts, as well as academic advisers from disciplines ranging from music, dance, art and anthropology. Throughout this period, his peers included many Indigenous leaders who would come to be celebrated over the following decades as fighters for justice and champions of land rights.1 Dick had every reason to be confident of his stature among them and, in 1974, he would become the first Chair of the fully Indigenous Aboriginal Arts Board (under Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s new larger Australia Council).

In 1970s Sydney, Dick was a charming, warm, urbane presence. He was a frequent visitor to our menagerie of a household in Glebe, where a rolling number of itinerants stayed for both short and long periods, including many artists. Sometimes lonely, Dick came for the company, the food and a few beers — around the kitchen table, his jocular, raconteuring manner produced numerous larger-than-life tales of his exploits. He was particularly close with Dr Thancoupie Gloria Fletcher (Thanakupi), an artist from Weipa, who was also kin and became one of the country’s most respected ceramicists. Dick was older by 15 years, but they talked incessantly of their families. Thancoupie — whom Dick always called Gloria, or ‘my gel’ — listened eagerly to his updates on his wife Elsie and their six children on Mornington Island.

Dick was in his mid-forties at the time I met him, but these years in Sydney were a world away from where he grew up. After a fully self-sufficient hunting life on Mornington Island in his youth — surviving on turtle, shellfish, fishing and spearing game — Dick also worked on cattle stations at Tallawanta, Gregory Downs and Lorraine Station (where the food was so bad he took off on foot to Burketown and was police-escorted back to Mornington Island). He was a stockman and ringer, mustering, dipping, branding and droving long distances with pack horses. He was also an experienced deckhand on the Cora — which travelled across the Gulf to the east coast of the Northern Territory, Mornington Island, Aurukun and Weipa — and he enjoyed the open air and the smell of the sea.

Related: Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey

However, this was still the era Aboriginal people call the ‘Dog Act’ times; in order to leave Mornington Island to work on cattle stations, Dick needed a permit to leave — a ‘dog tag’.2 He mostly avoided this through misdeeds and purposely stealing cattle, hoping to be sent to Palm Island, from which he imagined he could run away. From the adventures he regaled us with, and from his autobiography, it is clear that his larrikin nature and determined personality repeatedly led him to try to escape island life — dominated by the mission — to a life offering greater and more exciting opportunities. But World War Two intervened, and his theft was forgiven by default when the cattle stations called for men in wartime and he was suddenly sent out to work them. During the war years, he also assisted in the location and recovery of wreckage and human remains from American planes that crashed in the Gulf. He married Elsie at the Presbyterian Church on Mornington Island in September 1944.

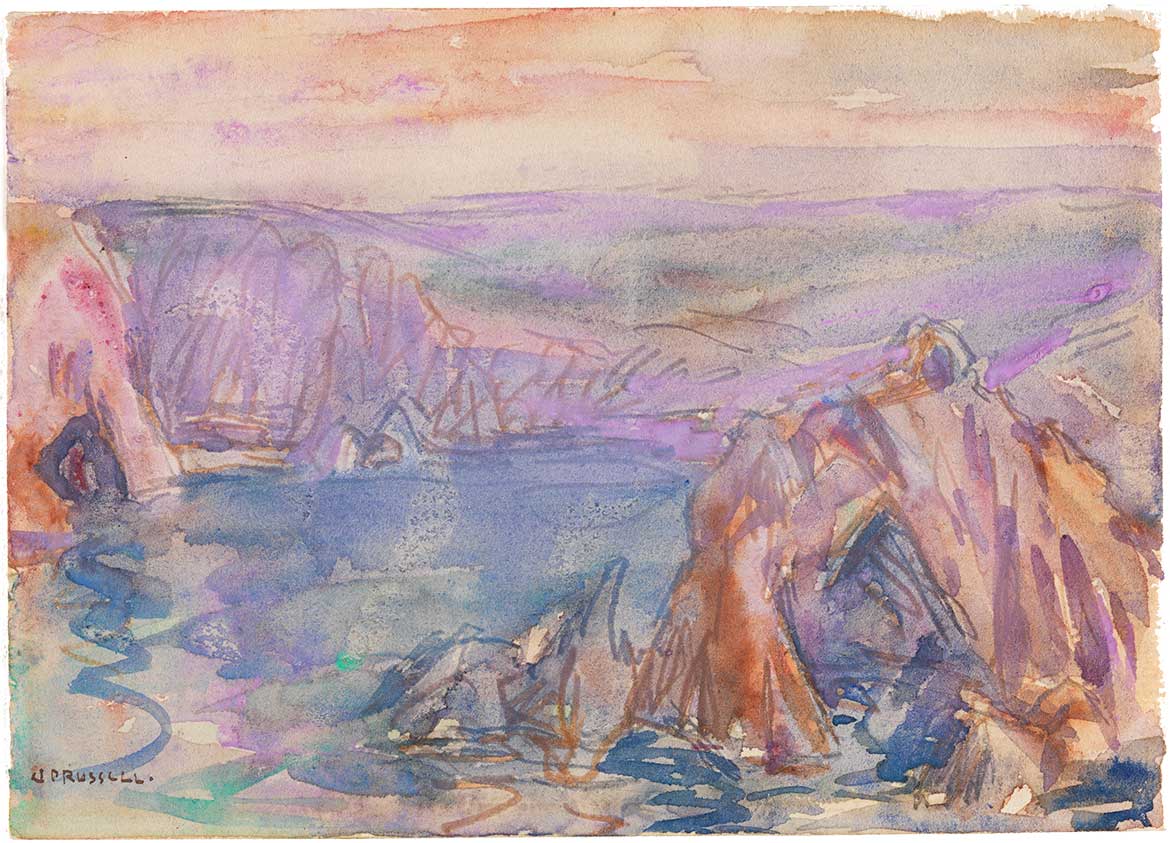

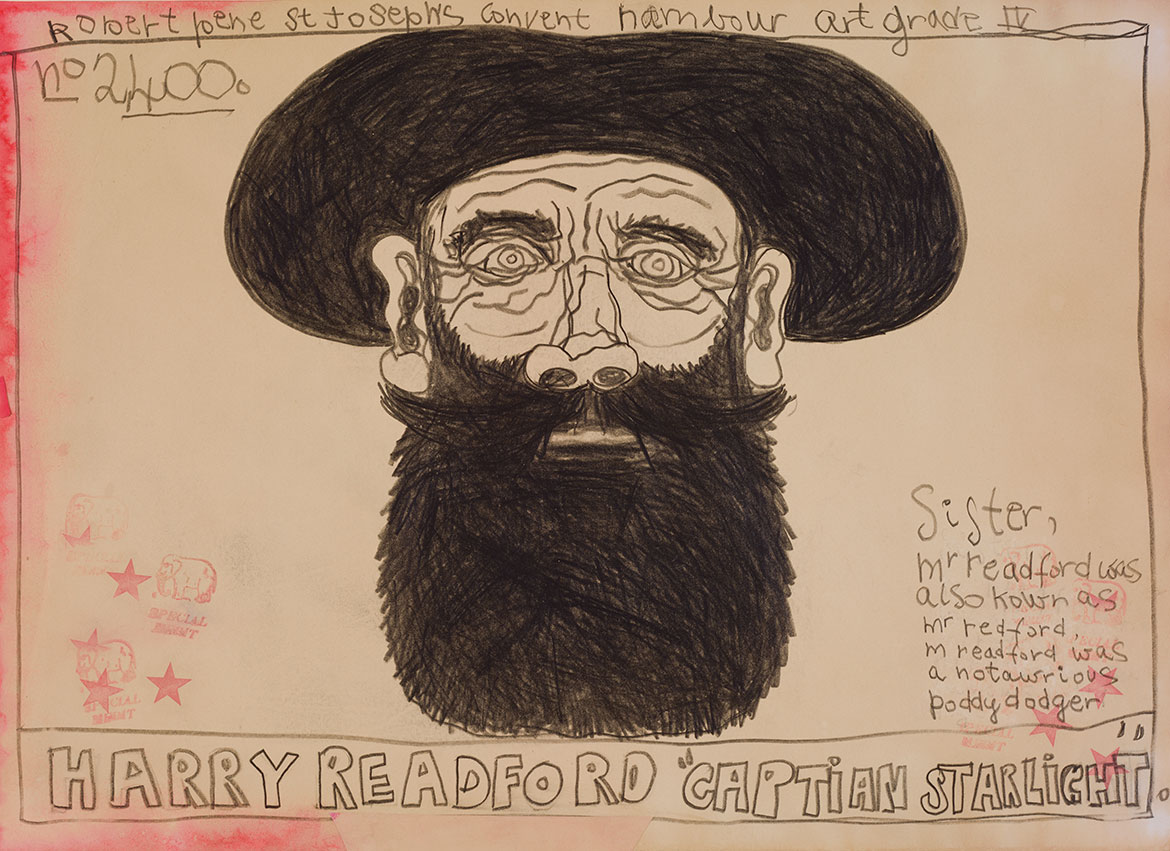

Throughout the 1950s, Dick worked on the mainland and also lived at the mission during the wet season. By 1960, he and his elder brother Lindsay (Burrud) began painting barks as well as carving utensils, spears and artefacts. Unlike Arnhem Land bark paintings, Lardil works were quite figurative, and primarily done in sequenced vignettes — like comic books — that told a cautionary tale or Creation story. These stories were well known to people of Dick’s age, but it concerned him that the younger generation ignored them. He frequently attached his own handwritten explanations on the back of the bark paintings.

Dick’s bark works featured ceremonial scenes relating to aspects of love magic (Djarada), flood, birth, initiation, burial practices and punishment for transgression of the laws. Realistic figures appear frozen in action but bear the full repertoire of Lardil body paint designs, wearing ceremonial hats, cockatoofeather head bands and woven arm bands. They are shown in silhouette or in profile, often in shake-a-leg dance position or poised ready to hurl weapons. The figures are arranged in tiers, sometimes with an inventory of Lardil artefacts and weapons.

In 1962, Dick was a yardman at the lodge in Karumba, the only town in Gulf Country that sits right on the coast — extensive tidal flats and shifting sands make other coastal settlement impossible in the region. As a pilot for Ansett, Percy Trezise often stopped overnight in Karumba on his route across the Gulf. The two men struck up a friendship through painting when the manager of the lodge commissioned Percy to paint a mermaid on the floor of the swimming pool. Percy would later become one of the strongest influences on Dick’s practice and career, and a catalyst for his journey into the mainstream art world. Percy particularly encouraged Dick to paint his own cultural knowledge and stories, rather than to try to emulate the work of Albert Namatjira, whose art was hugely popular and who was Dick’s personal hero.

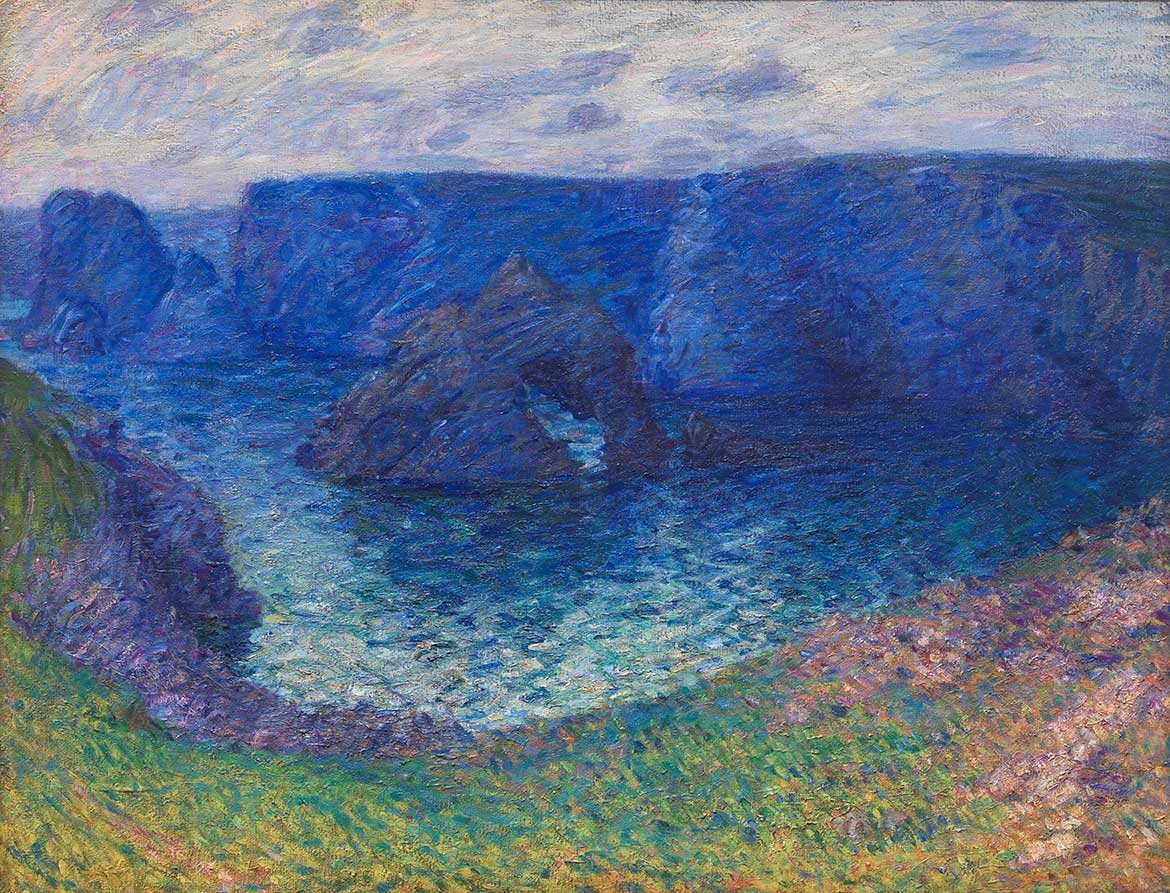

Dick and Percy began going on frequent camping trips on the Cape York Peninsula to paint and to map cave paintings in the sandstone escarpment. Dick’s consultations with traditional owners — particularly Willy Long, who lived in a corrugated tin-shack settlement a few miles from Laura — enabled him to record the mythological meanings of many of the cave images and to discuss the consistencies with his own Lardil stories. The Rainbow Serpent often featured in his paintings, along with the giant dog or dingo. When, on Percy’s advice, Dick turned to other media, he began exploring hunting images, with lyrical and romantic depictions of gathering firewood, hunting turtles, or swimming among the water lilies in blue lagoons.

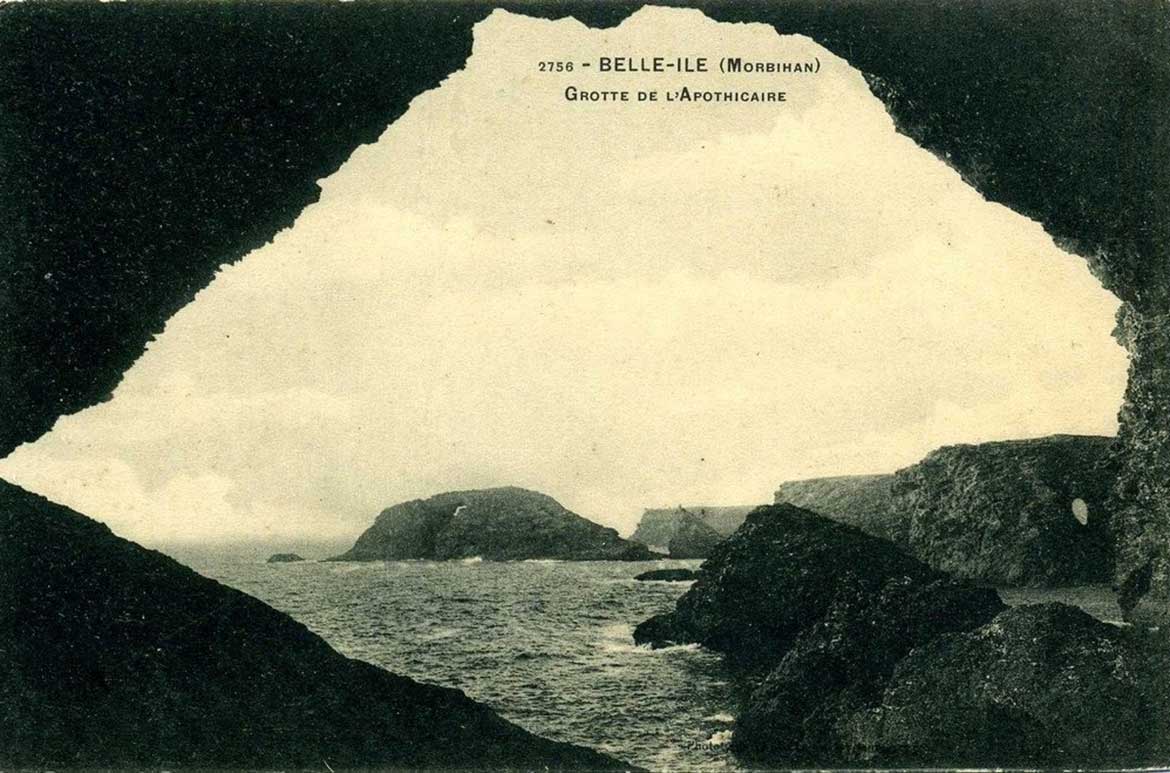

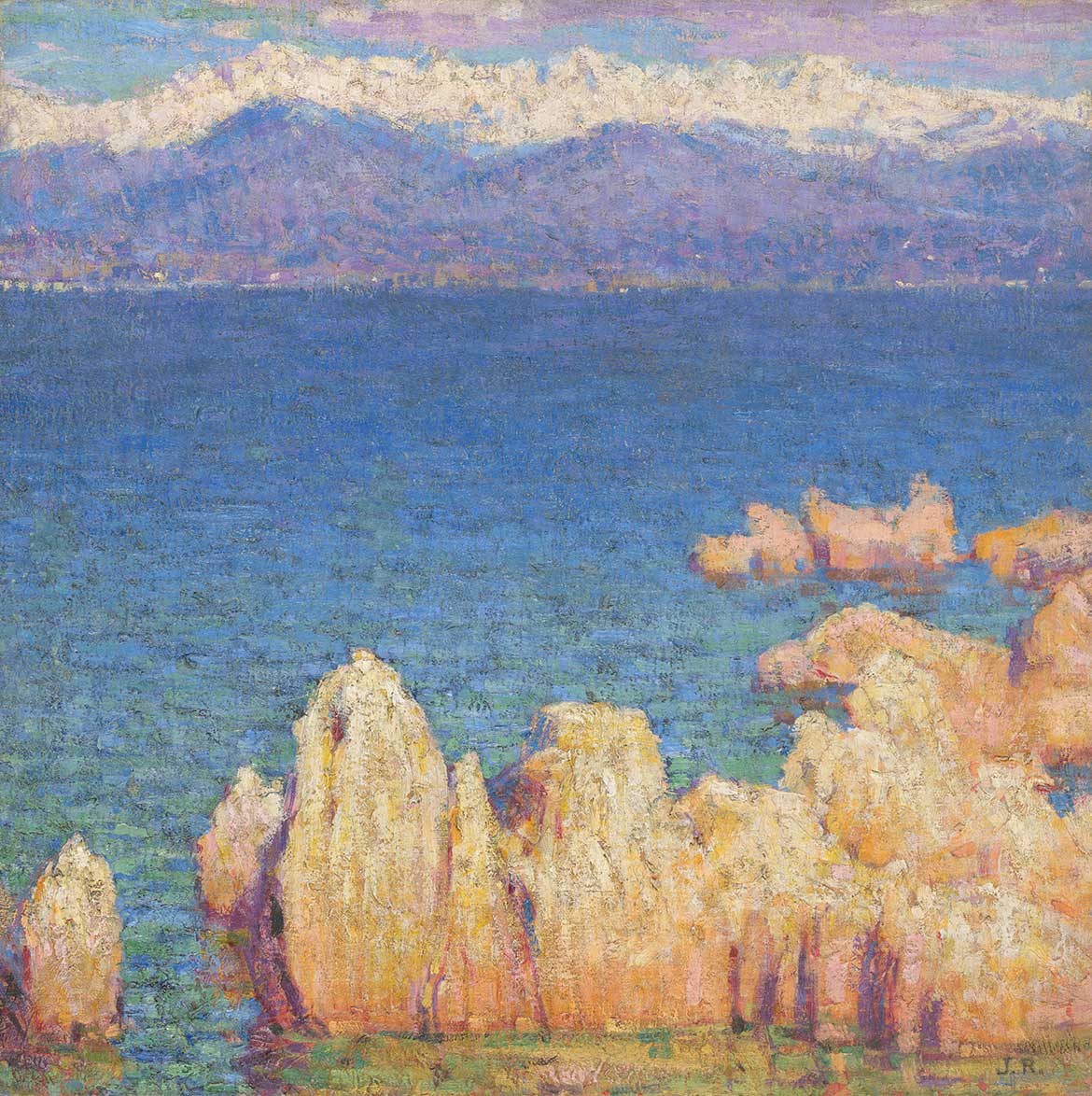

Renowned artist Ray Crooke was another important mentor in Dick’s life, and Dick, Percy and Ray developed a tight camaraderie on their bush painting adventures. Crooke strongly influenced Dick with his advanced knowledge of oil painting technique, which is evident in Dick’s depictions of life vignettes using strong bodily form, rounded dark figures and sensuous tropical colour. Whereas Dick’s bark paintings were two-dimensional, his shift to working with oils and acrylics on Masonite or artists’ board introduced perspective both in the figures and in the landscape. The new medium enabled Dick to make thematic series portraying historical events, including the ill-fated 1848 expedition to the tip of Cape York by Edmund Kennedy and his Aboriginal guide, Jackey Jackey. As Percy’s son, Steve Trezise, observed while watching the men paint together: ‘Ray introduced the word chiaroscuro and kept saying, “More white, more white, mix it”, to assist Dick to achieve a middle ground in his landscape perspectives’.

Dick moved to Cairns in 1964 and continued to produce enough work for his paintings to be exhibited in shows around the country.3 In the early 1970s, he began working in the genre he became best known for, the stories and vivid illustrations for his children’s books, including The Giant Devil Dingo (1973) and The Rainbow Serpent (1975). These were followed by a series relating to the Quinkan (spirit) figures in the cave art he was so familiar with, and other fearsome characters in the legends. Percy was integral to this work and he co-authored the later books in the series, which enraptured Australian school children for two decades and were among the first books to introduce Aboriginal culture to children.

Late in his life, Dick was badly afflicted by trachoma. This eye condition frustrated and worried him, and he painted less. As tastes in art, and specifically Indigenous art, swerved towards the new, modern, colourful acrylics of the desert, opportunities faded for sell-out shows of his work. To unaware new collectors, his paintings seemed folksy, naive or didactic. He returned to Mornington Island where he passed away from cancer in 1985.

Dick Roughsey’s pioneering life is an extraordinary and unique Australian story. He was one of ‘the first heroes’, an adventurer, a traveller between so many worlds — black and white, yet also mission and city, urban and village, and through the spiritual worlds of other ‘tribes’. He was brave and determined, yet also a very gifted artist who set high standards for others.

Jennifer Isaacs AM is a writer, art consultant and independent curator. She was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2003 in recognition of her work promoting Aboriginal culture and assisting Aboriginal artists.

Endnotes

1 These included painter Wandjuk Marika, the protagonist in the first land rights case; poet, playwright and musician George Winungwidj; writer, poet and activist Kath Walker (Oodgeroo Noonucal); community leader and first Aboriginal subject of a published autobiography, Phillip Roberts; union leader Chicka Dixon; land rights campaigner Eddie Mabo; and writer Jack Davis.

2 The Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act 1939 became known as the ‘Dog Act’ for its restrictions on human rights and freedoms. It prevented free movement, made possession or use of alcohol illegal, excluded ATSI people from voting rights and curtailed rights to own land and access justice. Under this law, people were settled away from their land by force, children were removed, certain marriages were forbidden and other injustices were perpetrated. On missions, the manager or superintendent determined suitable work and set the wage (usually low) and could seize property.

3 Exhibitions of Dick Roughsey’s work were held at various spaces during his career, including the Upstairs Gallery, Cairns; Artarmon Gallery, Wagner Art Gallery and Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney; Macquarie Galleries, Canberra; Australian Galleries, Melbourne; Bonython Gallery, Adelaide; and Anvil Gallery, Albury.

Subscribe to YouTube to go behind-the-scenes / Watch or Read about the Australian Collection

‘Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey: Stories of this Land’ is a collaboration between Cairns Art Gallery and QAGOMA.

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the Turrbal and Yugara (Jagera) peoples who are the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name or reproduce photographs of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Feature image detail: Dick Roughsey Strange procession passing by (from ‘Jackey Jackey and Kennedy’ series) 1983

#DickRoughsey #QAGOMA

Copyright © 2008

This feed is for personal, non-commercial use only.

The use of this feed on other websites breaches copyright. If this content is not in your news reader, it makes the page you are viewing an infringement of the copyright. (Digital Fingerprint:

)